How The Ethnic Makeup Of Cuba Changed After The Revolution

Racism in Republic of cuba refers to racial discrimination in Republic of cuba. In Cuba, dark skinned Afro-Cubans are the just group on the island referred to as blackness while lighter skinned, mixed race, Afro-Cuban mulatos are often non characterized as black. Race conceptions in Cuba are unique because of its long history of racial mixing and appeals to a "raceless" order. The Cuban demography reports that 65% of the population is white while foreign figures report an approximate of the number of whites at anywhere from 40 to 45 percent.[1] This is likely due to the self-identifying mulatos who are sometimes designated officially as white.[ii] Many Cubans argue that every Cuban has at least some African ancestry. Several pivotal events have impacted race relations on the island. Using the historic race-blind nationalism beginning established around the fourth dimension of independence, Cuba has navigated the abolition of slavery, the suppression of black clubs and political parties, the revolution and its aftermath, and the current economic decline.

History [edit]

Slavery and Independence [edit]

American analogy showing a black slave driver whipping a black slave in Cuba.

According to Voyages – The Transatlantic Slave Merchandise Database,[three] most 900,000 Africans were brought to Cuba as slaves. To compare, some 470,000 Africans were brought to what is now the U.s.a., and v,500,000 to the much vaster region of what is now Brazil.

As slavery was abolished or restricted in other areas of the Americas during the 19th century, the Cuban slave trade grew dramatically. Only between 1790 and 1820, 325,000 Africans were brought to Republic of cuba, quadruple the number from the people brought in the last 30 years.[4] The abolitionism of slavery was a gradual process that began during the outset war for independence. On October x, 1868, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, a plantation owner, freed all of his slaves and asked them to bring together him in liberating Cuba from Spanish occupation.[five] In that location were many small rebellions in the side by side several decades which led Spain to counteract. Spanish propaganda convinced white Cubans that independence would only pave the way for a race war; That Afro-Cubans would take their revenge and conquer the island. At this time, many white colonists were terrified that the Haitian revolution would occur elsewhere, similar in Cuba.[5] [six] [vii] This fear of a black revolt painted perceptions about racial justice and stalled progress in race relations for the next several decades, if not still prevalent today.

In order to abnegate this claim, anti-racism activists and politicians of the fourth dimension created the image of the loyal black soldier who existed merely to serve the independence movement. This conception that painted Cubans of color as obedient, and single-mindedly in favor of independence was the opposite of the savage, sexually ambitious stereotype of Castilian propaganda. Afterwards this, whites were persuaded to call up that considering the independence movements helped to end slavery, that there was no reason for a blackness revolt; blackness people ought to be thankful for their liberty. And further, race was an invented obstruction according to the influential thinkers of the twenty-four hours. It was in these years that the ideas of José Martí or the words of Full general Antonio Maceo, "no whites nor blacks, only only Cubans" took concord on the isle.[five] [vi] These 2 iconic figures represented blackness and white cooperation, and raceless Cuban patriotism. To this day, many Cubans argue that race equally a concept only exists to divide; information technology isn't real.[viii] Following the abolition of slavery, Afro-Cubans joined the armed forces in droves to fight confronting the colonial occupation of Spain. At least half of all soldiers who fought in the wars for independence were Afro-Cuban.[9]

Independent Party of Color [edit]

In 1908, Evaristo Estenoz and Pedro Ivonet, ii veterans from the independence wars, created the Partido Independiente de Colour (Independent Political party of Color, or PIC) as the get-go political political party for non-white Cubans. In the aftermath of the Cuban war of independence, Afro-Cuban men, many of whom were veterans, expected a singled-out shift in racial politics on the island subsequently Espana was no longer in charge.[10] This was due especially to the substantial impact the Afro-Cuban community fabricated to the war try. In the subsequent decades, Afro-Cubans watched as white citizens and immigrants enjoyed economical stability while the blackness population grew more dissatisfied. Clearing was restricted to Spanish built-in persons in an effort to whiten (blanqueamiento) the island.[ii] [6] This was a measure heavily supported past the United States who had a vested interest in Cuba's economical well-being.

In response and due to the race blind ideology of racial liberation created by Jose Marti and Full general Maceo, white Cubans were furious that a political political party based on racial identity existed on the island. The Flick was called racist and exclusionary; they accepted white members but only elected black leaders to the political party. The party was met with heavy backfire. Many white Cubans claimed that the institution of a party based on race was itself racist. In 1910, Senator Martín Morúa Delgado, mulato himself, presented and helped laissez passer a police force to ban race-based political parties, finer outlawing the PIC.[11] [12] The members of the Motion-picture show were not happy about this news. In 1912, many Afro-Cubans took to the streets in armed protest against this police. Sources vary on the original organizers of the protest that occurred as a result of this ban. In response, President Machado ordered the military machine to end the rebellion, violently if necessary. Joined by private white militias, the national baby-sit proceeded to kill between 3000 and 7000 Afro-Cubans, some of whom were non involved in the insurgence at all. This massacre, oftentimes chosen the Footling Race War or State of war of 1912, cloaked the tone of race conversation for decades to come.

Cuban Revolution [edit]

The revolution of 1959 inverse race relations drastically. Institutionally speaking, Cubans of Colour benefited disproportionately from revolutionary reform. After the overthrow of the Batista regime, Fidel Castro established racism as one of the central battles of the revolution.[13] Though Cuba never had formal, state sanctioned segregation, privatization disenfranchised Cubans of color specifically.[12] Previously white only private pools, beaches, and schools were made public, complimentary, and opened upward to Cubans of all races and classes. Because much of the Afro-Cuban population on the island was impoverished before the revolution, they benefited widely from the policies for affordable housing, the literacy programme, universal free teaching in full general, and healthcare.[14] But to a higher place all, Castro insisted that the greatest obstacle for Cubans of color was access to employment. By the mid 1980s racial inequality on paper was nearly nonexistent. Cubans of color graduated at the same (or college) rate equally white Cubans. The races had an equal life expectancy and were every bit represented in the professional arena.[12] [15]

When Fidel Castro seized power of Cuba in 1959, his administration quickly got to work. They passed more than than 1500 legislative pieces during the offset thirty months. These laws included priorities such every bit education, poverty, country distribution, and race. However, Castro's arroyo to race and eliminating racial divides was to make Republic of cuba a raceless nation, rather focusing on people'southward Cuban identity and eliminating the perception of race all together. It was an anti-bigotry campaign in its purest form, at that place could be no bigotry of races if there was a raceless state, merely Cubans.

The revolutionary government aligned itself with the race-bullheaded narrative historically embedded in Cuba's race relations. And because of this, Castro refused to enact laws that directly addressed and condemned race based persecution because he considered them unnecessary or even anti-Cuban. Instead, he believed that fixing economic structures for a meliorate distribution of wealth would cease racism. Castro's revolution also employed the use of the loyal black soldier of the independence days in society to adjourn white resistance to the new policies.[12] Scholars argue that raceless rhetoric left Republic of cuba unprepared to address the deep-seated culture of racism on the isle. Two years after his 1959 speech at the Havana Labor Rally, Castro declared that the age of racism and bigotry was over. In a speech given at the Confederation of Cuban Workers in observance of May Twenty-four hour period, Castro declared that the "only laws of the Revolution ended unemployment, put an end to villages without hospitals and schools, enacted laws which ended bigotry, command by monopolies, humiliation, and the suffering of the people."[16] Subsequently this announcement, any attempt by Afro-Cubans to open up give-and-take on race again was met with corking resistance. If the regime claimed that racism was gone, an endeavour to reignite the conversation on race was thus counterrevolutionary.

Though Castro'due south vision for Cuba was to non see color, a concept which many today view as futile, he addressed racial bigotry and inopportunity by converting previously segregated and "white only" spaces to integrated spaces. Black Cubans and mulatos got admission to opportunities not possible under Batista. At that place was education and employment opportunities, even gaining access to recreational facilities and beaches. [17]

Castro's government promised to get rid of racism in three years, despite Cuba'due south tearing history of colonialism. In January of 1959, the regime's official newspaper, Revolución, the championship of this edition was "Not Blacks, only Citizens".[xviii] This can be critiqued due to the framing of this campaign and title that in order to be a citizen, Blackness Cubans could non hold on to their Blackness identity. In order for them to be integrated into Castro'southward new guild, they were expected to simply exist Cuban. This is not something that Blackness Cubans could easily do, every bit it shaped their lives on the island. Blackness Cubans notwithstanding experienced employment discrimination, especially when their economic system relied on tourism, and they experienced more challenging conditions when in poverty.

Some statistics evidence the successes of this approach to anti-racism in Cuba. Some critique the Cuban Revolution for entering the voices of white revolutionaries and not enough Black leaders, fifty-fifty though they acknowledge that they were at the table. Republic of cuba, by 1980, had equal life expectancy rates of Blackness and White people, a stark contrast from the The states and Brazil who had large inequalities in terms of life expectancies. [19]

Special Menstruum [edit]

With the reintroduction of capitalist practices to the isle due to the fall of the Soviet Wedlock and subsequent economical depression in the late 80's and early xc'due south, Afro-Cubans have institute themselves at a disadvantage. Because the majority of those that emigrated from Republic of cuba to the U.s.a. were heart class and white, Cubans of color nonetheless on the island were far less likely to receive remittances—dollars gifted from relatives in the United States.[2] [7] With a costless market came private businesses. The majority of which were from western countries with distinct racial biases of their own. Because of this, less Afro-Cubans were hired to work in the rising tourist sector. Hiring practices favored applicants with buena presencia, or skilful appearance, that adheres to European standards of dazzler and respectability, therefore lighter-skinned or white Cubans were favored past foreign run establishments.[12] Similarly, in housing, despite improvements, racial difference persists due to various causes, such as inequality in house buying inherited from before the revolution and black people's "lack of resources and connections."[12] The Afro-Cubans interviewed by Sawyer, even when they complained of racism and government policies, expressed their conviction that "things would be worse under the leadership of the Miami exile customs or in the The states," and that "[t]he revolution has done so much for united states of america." This "provide[s] Afro-Cubans with a reason to back up the current regime."[20]

The Debate [edit]

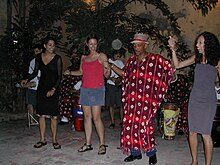

A Cuban human of color teaching an Afro-Cuban trip the light fantastic.

At that place is heavy debate today on how the 1959 revolution impacted race relations on the isle. Overall, the debate of racism in Cuba typically takes one of two extremes. Either the revolution ended racism, or it exacerbated or even created racial tension on the island.[13] Many scholars of race in Cuba take a far more qualifying position that while the revolution helped Afro-Cubans, it as well halted whatsoever farther racial progress beyond institutionalization.

The Revolution Ended Racism [edit]

Typically the proponents of the elimination of racism position are close to the revolutionary government, supportive of the revolution in total, and/or come from an older generation of Cubans that are more familiar with pre-revolutionary racism.[2] [21] They argue that the dismantling of economic form through socialism destroyed the material perpetuation of racism.[22] In 1966, Castro himself said that, "Discrimination disappeared when class privileges disappeared."[seven] Castro also frequently compared the anti-racism of Republic of cuba to the United States' segregation, and labeled Cuba equally a "Afro-Latin" nation when justifying anti-purple support to liberation fronts in Africa.[2]

Graffiti in Havana, 2017.

Many[ who? ] who fence that Cuba is non racist base their claims on the idea of Latin American Exceptionalism. According to this argument, a social history of intermarriage and mixing of the races is unique to Latin America. The large mestizo populations that issue from high levels of interracial union common to the region are ofttimes linked to racial republic. For many Cubans this translates into an argument of "racial harmony," often referred to as racial democracy. Co-ordinate to Mark Q. Sawyer, in the case of Cuba, ideas of Latin American Exceptionalism have delayed the progress of true racial harmony.[23]

The Revolution Silenced Non-white Cubans [edit]

While many opponents of the revolution, such equally Cuban emigrants, argue that Castro created race problems on the island, the about common claim for the exacerbation of racism is the revolution's inability to accept Afro-Cubans who want to merits a black identity.[22] After 1961, information technology was only taboo to talk about race at all.[12] Antiracist Cuban activists who rejected a raceless approach and wanted to show pride in their blackness such as Walterio Carbonell and Juan René Betancourt in the 1960s, were punished with exile or imprisonment.[ii] [12]

Esteban Morales Domínguez, a professor in the University of Havana, believes that "the absence of the debate on the racial trouble already threatens {...} the revolution's social project."[24] Carlos Moore, who has written extensively on the issue, says that "there is an unstated threat, blacks in Cuba know that whenever you heighten race in Cuba, y'all go to jail. Therefore the struggle in Republic of cuba is different. In that location cannot be a civil rights movement. Yous will have instantly ten,000 black people dead."[24] He says that a new generation of black Cubans are looking at politics in some other way.[24] Cuban rap groups of today are fighting against this censorship; Hermanos de Causa explains the problem all-time by proverb, "Don't you tell me that at that place isn't any [racism], because I have seen it/ don't tell me that information technology doesn't exist, because I accept lived it."[25]

Meet also [edit]

- Homo rights in Cuba

- Politics of Republic of cuba

References [edit]

- ^ Carlos Moore. "Why Republic of cuba'southward white leaders feel threatened by Obama".

- ^ a b c d e f Schmidt, Jalane D. (2008). "Locked Together: The Culture and Politics of 'Blackness' in Cuba". Transforming Anthropology. 16 (2): 160–164. doi:10.1111/j.1548-7466.2008.00023.x. ISSN 1051-0559.

- ^ Voyages – The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database Archived 2013-10-27 at the Wayback Auto

- ^ Ferrer, Ada (2008). "Cuban Slavery and Atlantic Antislavery". Fernand Braudel Middle Review. 31: 267–295 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c Ferrer, Ada (1999). Insurgent Republic of cuba: Race, Nation, and Revolution, 1868-1898. The University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ a b c Torre, Miguel A. De La (2018-05-04). "Castro's Negra/os". Black Theology. 16 (two): 95–109. doi:10.1080/14769948.2018.1460545. ISSN 1476-9948.

- ^ a b c Ravsberg, Fernando (2014). "Cuba's Awaiting Racial Debate". Afro-Hispanic Review. 33 (one): 203–204. ISSN 0278-8969.

- ^ Benson, Devyn Spence (2016-04-25). Antiracism in Cuba. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN978-i-4696-2672-7.

- ^ Pérez, Louis A. (1986). "Politics, Peasants, and People of Color: The 1912 "Race War" in Cuba Reconsidered". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 66 (3): 509–539. doi:10.2307/2515461. ISSN 0018-2168.

- ^ Helg, Aline (2009-04-20), "Republic of cuba, Anti-Racist Movement and the Partido Independiente de Color", The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest, Oxford, Great britain: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. i–five, ISBN978-1-4051-9807-3 , retrieved 2020-11-22

- ^ Eastman, Alexander Sotelo (2019-02-23). "The Neglected Narratives of Cuba's Partido Independiente de Color: Civil Rights, Popular Politics, and Emancipatory Reading Practices". The Americas. 76 (i): 41–76. ISSN 1533-6247.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Benson, Devyn Spence (2017-01-02). "Conflicting Legacies of Antiracism in Cuba". NACLA Report on the Americas. 49 (1): 48–55. doi:10.1080/10714839.2017.1298245. ISSN 1071-4839.

- ^ a b de la Fuente, Alejandro (2001). "Building a Nation for All". A Nation for All: Race, Inequality, and Politics in Twentieth-century Cuba. The University of North Carolina Printing. pp. 259–316. ISBN978-0-8078-9876-five.

- ^ Perez, Louis A.: Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution, New York, NY. 2006, p. 326

- ^ Weinreb, Amelia Rosenberg (2008). "Race,Fé(Faith) and Republic of cuba'southward Hereafter". Transforming Anthropology. sixteen (ii): 168–172. doi:10.1111/j.1548-7466.2008.00025.x. ISSN 1051-0559.

- ^ Speech given by Fidel Castro on April 8, 1961. Text provided by Havana FIEL Network

- ^ Benson, Devyn Spence (2016). ""Non Blacks, Just Citizens": Race and Revolution in Cuba". Earth Policy Journal. 33 (i): 23–29. ISSN 1936-0924.

- ^ Benson, Devyn Spence (2016). ""Non Blacks, Merely Citizens": Race and Revolution in Republic of cuba". World Policy Periodical. 33 (1): 23–29. ISSN 1936-0924.

- ^ de la Fuente, Alejandro (1995-01-01). "Race and Inequality in Cuba, 1899-1981". Journal of Contemporary History. 30 (1): 131–168. doi:10.1177/002200949503000106. ISSN 0022-0094.

- ^ Sawyer, pp. 130–131

- ^ de la Fuente, Alejandro (1995). "Race and Inequality in Republic of cuba, 1899-1981". Periodical of Contemporary History. xxx (1): 131–168. ISSN 0022-0094.

- ^ a b Lusane, Clarence (2003). "From Black Cuban to Afro‐Cuban:Researching Race in Cuba". Souls. 1 (2): 73–79. doi:10.1080/10999949909362164. ISSN 1099-9949.

- ^ Marking Sawyer. Racial Politics in Mail-Revolutionary Cuba.

- ^ a b c "A barrier for Cuba's blacks". Miami Herald.

- ^ de la Fuente, Alejandro (2011). "The New Afro-Cuban Cultural Motility and the Contend on Race in Gimmicky Cuba". Journal of Latin American Studies. forty (4): 697–720. doi:10.1017/s0022216x08004720. ISSN 0022-216X.

Books and papers [edit]

- "Race and Inequality in Republic of cuba Today" ( Raza y desigualdad en la Cuba actual ) by Rodrigo Espina and Pablo Rodriguez Ruiz

- "The Challenges of the Racial Problem in Cuba" ( Fundación Fernando Ortiz ) past Esteban Morales Dominguez

- Sujatha Fernandes, Fear of a Black Nation: Local Rappers, Transnational Crossings, and Land Power in Gimmicky Cuba, Anthropological Quarterly, Book 76, Number 4, Autumn 2003, pp. 575–608, E-ISSN 1534-1518 Print ISSN 0003-5491

- "Racism in Cuba: news virtually racism in Republic of cuba in English and Spanish (2006- )"

- Revolution and race: Blacks in contemporary Cuba by Lourdes Casal (1979)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Racism_in_Cuba

Posted by: cartervoiled.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How The Ethnic Makeup Of Cuba Changed After The Revolution"

Post a Comment